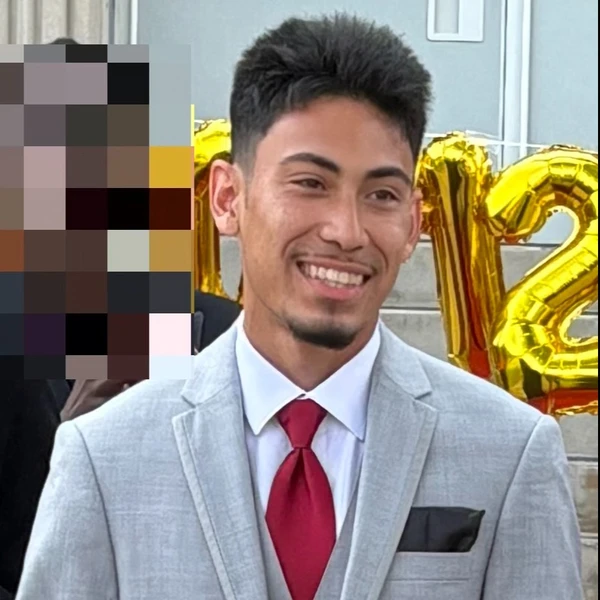

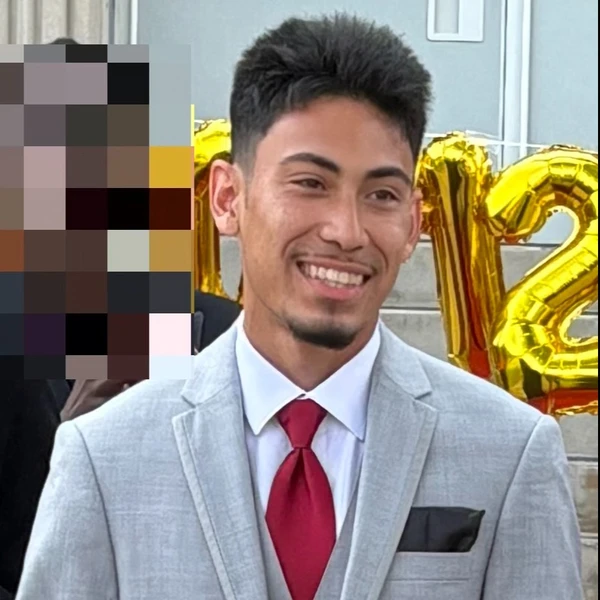

Romeo Yon

1,465

Bold Points1x

Finalist

Romeo Yon

1,465

Bold Points1x

FinalistBio

My name is Romeo, and I’m a senior at Rahway High School preparing to attend Rutgers University–New Brunswick this fall, where I’ll be majoring in Civil Engineering. I’m passionate about designing sustainable infrastructure and hope to help build smarter, more resilient cities that positively impact communities. Over the past four years, I’ve also been a dedicated member of my school’s varsity track and field team, which has taught me the value of discipline, persistence, and teamwork. Whether in athletics or academics, I’m always striving to grow, challenge myself, and make a meaningful difference in the world around me.

Education

Rahway High School

High SchoolMiscellaneous

Desired degree level:

Bachelor's degree program

Majors of interest:

- Civil Engineering

Career

Dream career field:

Civil Engineering

Dream career goals:

Sports

Track & Field

Varsity2021 – Present5 years

Track & Field

Varsity2021 – Present5 years

RonranGlee Literary Scholarship

“It’s disgraceful how humans blame the gods. They say their tribulations come from us, when they themselves, through their own foolishness, bring hardships which are not decreed by Fate. Now there’s Aegisthus, who took for himself the wife of Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, and then butchered him, once the man came home. None of that was set by Fate. Aegisthus knew his acts would bring about his total ruin. We’d sent Hermes earlier to speak to him. The keen-eyed killer of Argus told him not to slay the man or seduce his wife, for Orestes would avenge his father, once he grew up and longed for his own land. That’s what Hermes said, but his fine warning did not persuade Aegisthus in his heart. So he has paid for everything in full.”

In this early moment of The Odyssey, Zeus delivers a striking reflection on the human tendency to deflect blame onto divine forces. His words—“It’s disgraceful how humans blame the gods... when they themselves, through their own foolishness, bring hardships which are not decreed by Fate”—reveal Homer’s deeper assertion that human suffering is often self-inflicted, not divinely imposed. Far from helpless pawns in the clutches of destiny, human beings in The Odyssey are frequently the architects of their own downfall, and moral failure—rather than destiny—is the cause of this.

The case that Zeus presents is that of Aegisthus, who was a man who had seduced Agamemnon's wife and killed him when he came back. Zeus says that Aegisthus was not destined to have done this deed; indeed, the gods actually attempted to dissuade him from it. The divine messenger Hermes informed Aegisthus of the consequences of his actions—i.e., that Orestes would take revenge on him for killing his father. Aegisthus, however, disregarded this message and acted not in ignorance, as in not knowing, but in opposition. His punishment, then, was not fate catching up with him but justice for a choice made in full knowledge of its cost. The gods, in this case, did not interfere with his freedom to choose—they only reminded him of the moral law.

This passage compels a reassessment of how The Odyssey handles the concept of fate. Contrary to modern stereotypes that picture Greek epics as deterministic, Zeus maintains that individuals are miserable not because their destinies were preordained, but because they refuse to become wise or virtuous. The story of Aegisthus is a character and not a fate tragedy. Such an awareness redirects the gods from arbitrary puppetmasters to moral bystanders: they are not to control but to counsel.They guide and warn, but they do not coerce. In doing so, Homer gives human agency a central place in the epic’s moral universe.

Furthermore, Zeus’s frustration—calling it “disgraceful” that mortals blame the gods—suggests a broader ethical critique. It’s not just Aegisthus who acts badly; it’s the broader human impulse to externalize guilt, to avoid taking responsibility for one’s own actions. Homer, through Zeus, holds a mirror up to humanity and shows that evasion of blame is as corrosive as the sin itself. In a society deeply rooted in religious belief, the claim that mortals misuse divine narratives to excuse immorality is bold. It points to a timeless truth: blaming external forces for internal failures is a moral failure in itself.

In a modern context, this passage still resonates. Whether we blame systems, circumstances, or others for our own decisions, the danger remains the same: we risk losing the ability to grow by refusing to own our choices. Homer’s insight is not only ancient wisdom; it is enduring wisdom. By asserting that we are most often the authors of our misfortunes, he challenges readers to embrace accountability as a path to justice, and ultimately, to peace.