Hobbies and interests

Basketball

Artificial Intelligence

Exercise And Fitness

Business And Entrepreneurship

Physics

Aerospace

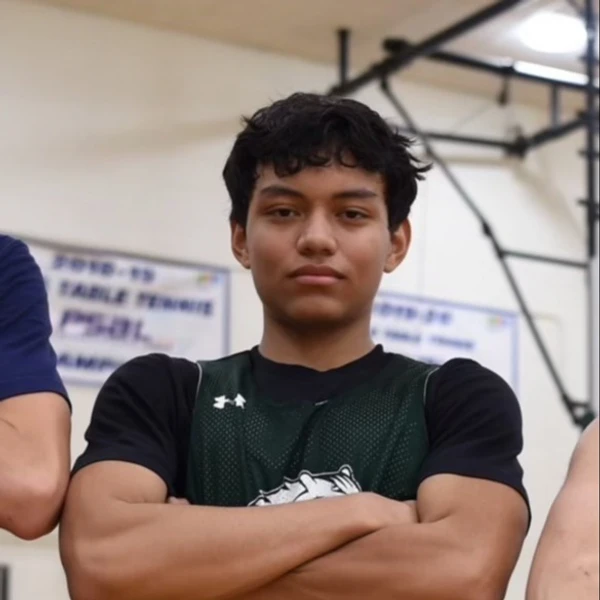

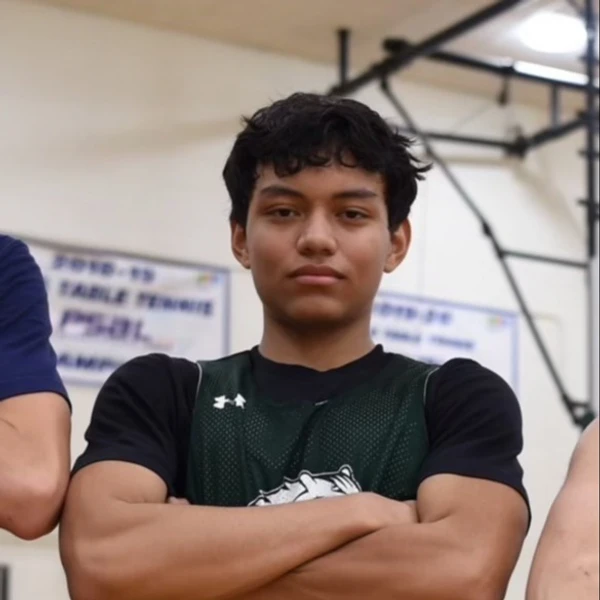

Abel Cepin

895

Bold Points1x

Finalist

Abel Cepin

895

Bold Points1x

FinalistBio

My name is Abel Cepin, and I’m a proud Hispanic student from the Bronx. I attended Bronx Science and will be heading to Cornell this fall, ready to take on new challenges in STEM. I’ve always loved building things—whether it was making contraptions in the back of my dad’s shop to make work easier or diving into physics and engineering to explore bigger ideas.

I’m fascinated by energy and aerospace, always thinking about how we can innovate for the future. Outside of academics, I was the captain of my basketball team, where I learned how to lead and push past expectations. I’m all about breaking barriers, whether on the court or in STEM, and I hope to open doors for others along the way.

Education

The Bronx High School of Science

High SchoolMiscellaneous

Desired degree level:

Master's degree program

Majors of interest:

- Engineering Physics

Career

Dream career field:

Aviation & Aerospace

Dream career goals:

NASA Engineer

Mentee

Quantum Information Science and Technology camp at Stony Brok2024 – 2024Mentee

Inspirit AI2024 – 2024Mentee

All Star Code2023 – 2023Mentee

The Knowledge Society2023 – 20241 yearLearner/Student

Rice University Pre-college: Space Exploration2024 – 2024Cashier/Laborer

California Fruit 183rd2020 – 20244 years

Sports

Basketball

Club2024 – 2024

Basketball

Junior Varsity2021 – 20232 years

Awards

- Most Imporved Player

Basketball

Varsity2023 – 20252 years

Awards

- Most Improved Player

Research

Cell/Cellular Biology and Anatomical Sciences

Stanley Manne Institute — Researcher2024 – 2024

Future Interests

Entrepreneurship

Abran Arreola-Hernandez Latino Scholarship

There are about 20 quadrillion ants in the world. I’d say that I’ve packed more peppers than ants in my lifetime: red, green, yellow, Shishito, Anaheim, long hot peppers—if you can name it, I’ve packed it. My pepper-packing career started in a supermarket on a street corner in Washington Heights. Black mold dotted the store’s ceiling while cabbage and kale camouflaged onto the floor’s black tiles. I remember punching in for my “shift,” still in my school uniform, then going to my “office,” a broom closet, dropping off my bag, and putting on my old, stained apron. I would head outside and wait in front of the store’s barely alive conveyor belt, watching boxes of red and green peppers fall into the rat-infested basement as my father threw more produce boxes at my feet. I would grab my box of plastic bags and whip one up and down, letting air fill it. Then, I would put two peppers in the bag, take the two ends of the opening, and spin the bag before tying the newly formed “laces” into a knot. I would throw the packed peppers into an empty banana box, then repeat the process. At first, I turned this monotonous task into something fun—calculating how many I packed per box or creating “math stories” using what I learned in school. But I outgrew the fun. I wanted bigger things to do; I had bigger dreams. But I viewed them as the horrors inside Pandora’s box. I thought my whole life would consist of tedious tasks, that I would pack peppers forever because my parents told me it was my purpose, engraving it into my mind. I’m the son of immigrant parents, a mother from Ecuador and a father from the Dominican Republic; they were chasing the “American Dream.” My mother sold batteries and hair ties on a street corner, and my father opened a humble supermarket with no more than 1,500 square feet. They chased the American Dream through labor that never rewarded them. My father told me I would do what he did—work in a supermarket and spend nights on a bedbug-infested couch—because dreams are for the weak and gullible. But my father was the weak one. He ran away to the DR last year and left me to dream. It’s okay, though. I had already unleashed my dreams (against his advice) when I got the opportunity to attend high school. It was a new world: club posters covered the walls, and there was a library. I had never seen a library in my life. Who knew there was more to the world than peppers? I saw being a learner as my new “job.” I took my job very seriously. Instead of packing peppers into bags, I packed new worlds into each bag: chemistry, U.S. history, statistics, and more. I fell in love with one world in particular: physics. From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electricity into sound using math, to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world but an entirely new universe. Spinning bags of peppers can’t compare to the hours spent finding the acceleration of a spinning top in physics. My new “office” was a classroom filled with 30 other dreamers, who helped my dreams take flight. I have not packed peppers for a little over a year; however, it was my years doing so that led me to yearn for more in life. I’m still a pepper packer, but now I pack the fruits of learning, and I will never cease doing so.

First-Gen Futures Scholarship

There are about 20 quadrillion ants in the world. I’d say that I’ve packed more peppers than ants in my lifetime: red, green, yellow, Shishito, Anaheim, long hot peppers—if you can name it, I’ve packed it. My pepper-packing career started in a supermarket on a street corner in Washington Heights. Black mold dotted the store’s ceiling while cabbage and kale camouflaged onto the floor’s black tiles. I remember punching in for my “shift,” still in my school uniform, then going to my “office,” a broom closet, dropping off my bag, and putting on my old, stained apron. I would head outside and wait in front of the store’s barely alive conveyor belt, watching boxes of red and green peppers fall into the rat-infested basement as my father threw more produce boxes at my feet. I would grab my box of plastic bags and whip one up and down, letting air fill it. Then, I would put two peppers in the bag, take the two ends of the opening, and spin the bag before tying the newly formed “laces” into a knot. I would throw the packed peppers into an empty banana box, then repeat the process. At first, I turned this monotonous task into something fun—calculating how many I packed per box or creating “math stories” using what I learned in school. But I outgrew the fun. I wanted bigger things to do; I had bigger dreams. But I viewed them as the horrors inside Pandora’s box. I thought my whole life would consist of tedious tasks, that I would pack peppers forever because my parents told me it was my purpose, engraving it into my mind. I’m the son of immigrant parents, a mother from Ecuador and a father from the Dominican Republic; they were chasing the “American Dream.” My mother sold batteries and hair ties on a street corner, and my father opened a humble supermarket with no more than 1,500 square feet. They chased the American Dream through labor that never rewarded them. My father told me I would do what he did—work in a supermarket and spend nights on a bedbug-infested couch—because dreams are for the weak and gullible. But my father was the weak one. He ran away to the DR last year and left me to dream. It’s okay, though. I had already unleashed my dreams (against his advice) when I got the opportunity to attend high school. It was a new world: club posters covered the walls, and there was a library. I had never seen a library in my life. Who knew there was more to the world than peppers? I saw being a learner as my new “job.” I took my job very seriously. Instead of packing peppers into bags, I packed new worlds into each bag: chemistry, U.S. history, statistics, and more. I fell in love with one world in particular: physics. From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electricity into sound using math, to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world but an entirely new universe. Spinning bags of peppers can’t compare to the hours spent finding the acceleration of a spinning top in physics. My new “office” was a classroom filled with 30 other dreamers, who helped my dreams take flight. I have not packed peppers for a little over a year; however, it was my years doing so that led me to yearn for more in life. I’m still a pepper packer, but now I pack the fruits of learning, and I will never cease doing so.

Ubuntu Scholarship

There are about 20 quadrillion ants in the world. I’d say that I’ve packed more peppers than ants in my lifetime: red, green, yellow, Shishito, Anaheim, long hot peppers—if you can name it, I’ve packed it. My pepper-packing career started in a supermarket on a street corner in Washington Heights. Black mold dotted the store’s ceiling while cabbage and kale camouflaged onto the floor’s black tiles. I remember punching in for my “shift,” still in my school uniform, then going to my “office,” a broom closet, dropping off my bag, and putting on my old, stained apron. I would head outside and wait in front of the store’s barely alive conveyor belt, watching boxes of red and green peppers fall into the rat-infested basement as my father threw more produce boxes at my feet. I would grab my box of plastic bags and whip one up and down, letting air fill it. Then, I would put two peppers in the bag, take the two ends of the opening, and spin the bag before tying the newly formed “laces” into a knot. I would throw the packed peppers into an empty banana box, then repeat the process. At first, I turned this monotonous task into something fun—calculating how many I packed per box or creating “math stories” using what I learned in school. But I outgrew the fun. I wanted bigger things to do; I had bigger dreams. But I viewed them as the horrors inside Pandora’s box. I thought my whole life would consist of tedious tasks, that I would pack peppers forever because my parents told me it was my purpose, engraving it into my mind. I’m the son of immigrant parents, a mother from Ecuador and a father from the Dominican Republic; they were chasing the “American Dream.” My mother sold batteries and hair ties on a street corner, and my father opened a humble supermarket with no more than 1,500 square feet. They chased the American Dream through labor that never rewarded them. My father told me I would do what he did—work in a supermarket and spend nights on a bedbug-infested couch—because dreams are for the weak and gullible. But my father was the weak one. He ran away to the DR last year and left me to dream. It’s okay, though. I had already unleashed my dreams (against his advice) when I got the opportunity to attend high school. It was a new world: club posters covered the walls, and there was a library. I had never seen a library in my life. Who knew there was more to the world than peppers? I saw being a learner as my new “job.” I took my job very seriously. Instead of packing peppers into bags, I packed new worlds into each bag: chemistry, U.S. history, statistics, and more. I fell in love with one world in particular: physics. From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electricity into sound using math, to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world but an entirely new universe. Spinning bags of peppers can’t compare to the hours spent finding the acceleration of a spinning top in physics. My new “office” was a classroom filled with 30 other dreamers, who helped my dreams take flight. I have not packed peppers for a little over a year; however, it was my years doing so that led me to yearn for more in life. I’m still a pepper packer, but now I pack the fruits of learning, and I will never cease doing so.

Mark Caldwell Memorial STEM/STEAM Scholarship

There are about 20 quadrillion ants in the world. I’d say that I’ve packed more peppers than ants in my lifetime: red, green, yellow, Shishito, Anaheim, long hot peppers—if you can name it, I’ve packed it.

My pepper-packing career started in a supermarket on a street corner in Washington Heights. Black mold dotted the store’s ceiling while cabbage and kale camouflaged onto the floor’s black tiles. I remember punching in for my “shift,” still in my school uniform, then going to my “office,” a broom closet, dropping off my bag, and putting on my old, stained apron. I would head outside and wait in front of the store’s barely alive conveyor belt, watching boxes of red and green peppers fall into the rat-infested basement as my father threw more produce boxes at my feet. I would grab my box of plastic bags and whip one up and down, letting air fill it. Then, I would put two peppers in the bag, take the two ends of the opening, and spin the bag before tying the newly formed “laces” into a knot. I would throw the packed peppers into an empty banana box, then repeat the process.

At first, I turned this monotonous task into something fun—calculating how many I packed per box or creating “math stories” using what I learned in school. But I outgrew the fun. I wanted bigger things to do; I had bigger dreams. But I viewed them as the horrors inside Pandora’s box. I thought my whole life would consist of tedious tasks, that I would pack peppers forever because my parents told me it was my purpose, engraving it into my mind.

I’m the son of immigrant parents, a mother from Ecuador and a father from the Dominican Republic; they were chasing the “American Dream.” My mother sold batteries and hair ties on a street corner, and my father opened a humble supermarket with no more than 1,500 square feet. They chased the American Dream through labor that never rewarded them. My father told me I would do what he did—work in a supermarket and spend nights on a bedbug-infested couch—because dreams are for the weak and gullible.

But my father was the weak one. He ran away to the DR last year and left me to dream. It’s okay, though. I had already unleashed my dreams (against his advice) when I got the opportunity to attend high school. It was a new world: club posters covered the walls, and there was a library. I had never seen a library in my life.

Who knew there was more to the world than peppers?

I saw being a learner as my new “job.” I took my job very seriously. Instead of packing peppers into bags, I packed new worlds into each bag: chemistry, U.S. history, statistics, and more.

I fell in love with one world in particular: physics. From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electricity into sound using math, to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world but an entirely new universe. Spinning bags of peppers can’t compare to the hours spent finding the acceleration of a spinning top in physics. My new “office” was a classroom filled with 30 other dreamers, who helped my dreams take flight.

I have not packed peppers for a little over a year; however, it was my years doing so that led me to yearn for more in life. I’m still a pepper packer, but now I pack the fruits of learning, and I will never cease doing so.

Sunshine Legall Scholarship

Erwin Schrödinger was just a name in my physics textbook until the second day of my quantum information program at Stony Brook. That was when I first heard about his famous thought experiment, Schrödinger’s cat. The idea that something could exist in two states at once until observed sounded impossible. I remember thinking to myself that there was genuinely no way for this to be true.

But as the week went on, I started to realize how wrong I was. Superposition wasn’t just some sci-fi baloney—it was the foundation for something world-changing. It was the reason I saw a future for myself in the energy field.

Before Stony Brook, I had only heard of quantum computers in passing while reading a few articles, but I didn’t understand just how much they could change the way we approach energy. Traditional computers are reaching their limit in what they can compute, as the size of bits can only get so small. We’ve gotten to the point where we have bits the size of atoms. Yet, even with all the bits in the world, we are stuck testing one possibility at a time.

However, quantum computers can process simulations thousands of times faster with a fraction of the hardware. The years of trial and error will be gone. Whether it’s finding the most efficient solar panel materials or optimizing energy grids, with quantum computing, the time needed could be condensed into days or even hours. The idea that quantum computing could completely reshape the way we develop sustainable energy solutions hooked me.

And then there’s space.

One of the biggest challenges with quantum computers is their need for freezing temperatures to function. So I immediately thought of space. What if we could send quantum computers into orbit, using the natural cold of space itself to keep them stable enough to operate effectively? I started thinking about how we could integrate them into satellites, processing massive amounts of data, improving communications, even helping us develop better energy solutions down on Earth.

I have no idea exactly how this would work yet, but that’s the best part. Where’s the fun in knowing how everything will work without trying it out?

I’ve fought for every inch of progress, and I will keep fighting for myself and those who come after me. I will step into spaces where Hispanics have been underrepresented—not just to take up space, but to make room for others. I will push past the expectations placed on me and prove that our voices, our stories, and our successes matter.

Moving forward, I refuse to be just another statistic, another story of potential left unrealized. I will continue to break barriers, challenge expectations, and uplift those who come after me. The Hispanic community is not just part of this country’s future—it is central to it.

Right now, everything I know is still theoretical. I haven’t had the chance to put these ideas into practice yet, but that’s why I’m here. I want to get my hands dirty in the labs that Cornell offers. I want to start putting my ideas into practice. I want to begin changing the world now—I can no longer wait.

There are problems in energy that haven’t been solved yet, solutions that haven’t even been imagined yet—I want to be the one to solve them.

It was Schrödinger who opened Pandora’s box when I learned of his theory, and now I find myself wanting to be the one who connects quantum physics, aerospace, and energy.

Why?

Because I saw a cat in a box once.

Jesus Baez-Santos Memorial Scholarship

There are about 20 quadrillion ants in the world. I’d say that I’ve packed more peppers than ants in my lifetime: red, green, yellow, Shishito, Anaheim, long hot peppers—if you can name it, I’ve packed it.

My pepper-packing career started in a supermarket on a street corner in Washington Heights. Black mold dotted the store’s ceiling while cabbage and kale camouflaged onto the floor’s black tiles. I remember punching in for my “shift,” still in my school uniform, then going to my “office,” a broom closet, dropping off my bag, and putting on my old, stained apron. I would head outside and wait in front of the store’s barely alive conveyor belt, watching boxes of red and green peppers fall into the rat-infested basement as my father threw more produce boxes at my feet. I would grab my box of plastic bags and whip one up and down, letting air fill it. Then, I would put two peppers in the bag, take the two ends of the opening, and spin the bag before tying the newly formed “laces” into a knot. I would throw the packed peppers into an empty banana box, then repeat the process.

At first, I turned this monotonous task into something fun—calculating how many I packed per box or creating “math stories” using what I learned in school. But I outgrew the fun. I wanted bigger things to do; I had bigger dreams.

But I viewed them as the horrors inside Pandora’s box. I thought my whole life would consist of tedious tasks, that I would pack peppers forever because my parents told me it was my purpose, engraving it into my mind.

I’m the son of immigrant parents, a mother from Ecuador and a father from the Dominican Republic; they were chasing the “American Dream.” My mother sold batteries and hair ties on a street corner, and my father opened a humble supermarket with no more than 1,500 square feet. They chased the American Dream through labor that never rewarded them. My father told me I would do what he did—work in a supermarket and spend nights on a bedbug-infested couch—because dreams are for the weak and gullible.

But my father was the weak one. He ran away to the DR last year and left me to dream.

It’s okay, though. I had already unleashed my dreams (against his advice) when I got the opportunity to attend high school. It was a new world: club posters covered the walls, and there was a library. I had never seen a library in my life.

Who knew there was more to the world than peppers?

I saw being a learner as my new “job.” I took my job very seriously. Instead of packing peppers into bags, I packed new worlds into each bag: chemistry, U.S. history, statistics, and more.

I fell in love with one world in particular: physics. From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electricity into sound using math, to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world but an entirely new universe. Spinning bags of peppers can’t compare to the hours spent finding the acceleration of a spinning top in physics. My new “office” was a classroom filled with 30 other dreamers, who helped my dreams take flight.

I have not packed peppers for a little over a year; however, it was my years doing so that led me to yearn for more in life. I’m still a pepper packer, but now I pack the fruits of learning, and I will never cease doing so.

Anthony Bruder Memorial Scholarship

For the longest time, I’ve been a basketball player. I remember the first time my dad took me to the courts—as I tried dribbling the ball, I must’ve looked like a baby taking their first steps. I played all throughout middle school, yet I never found myself on the school team, I was scared. I thought that if I messed up with a team that everyone would hate me, so I thought it’d be better to play alone. It would be in high school where this would change.

Once in high school, my mom essentially forced me to try out for the JV team at my school. Going into the tryout, I didn’t expect much since I had never played on a team before—yet I made the team,a decision that would completely alter my life’s path.

In my second year of high school, I became the team captain. As captain, I wasn’t just leading a school team—I was leading people. Our team was made up of a diverse group—Asian, White, and Black players—but I was the only Hispanic on the team. At first, I was scared, feeling as if being different from the rest would impact my ability to lead. I grew up in Washington Heights, a neighborhood notorious for its overwhelming Hispanic population. I wasn’t used to leading a group of people that didn’t look like me.

However, I knew that I had to prove myself as a leader, not just as an athlete. As captain, I learned that success isn’t achieved individually but as a whole. It’s about bringing people together, pushing past limits, and lifting others as you continue to climb. My experience on this team taught me that being a leader isn’t about the title attached to you, but about the action you can bring about.But more than leadership, basketball gave me something even more valuable—the ability to dream.

The support of my teammates, the camaraderie, and the feeling of pushing beyond what seemed possible filled me with a sense of purpose. Every time I stepped onto the court,I wasn’t afraid, instead I was in a world where limits didn’t exist, a world where I could shape outcomes through strategy, determination, and teamwork. In the same way that I visualized plays before they happened, I started to visualize something more—a future beyond the court. The game had expanded my imagination, making me believe in possibilities I had never considered before. Before long I was introduced to a new world: physics.

Just as basketball had expanded my imagination, physics gave it direction.From how speakers utilize electromagnetic waves to convert electrical energy into sound using math to how the creation of everything modern is built upon mathematical principles—this wasn’t just a new world, but an entirely new universe. The same excitement I felt designing plays and predicting outcomes on the court, I now felt when solving equations and unraveling the mechanics behind the physical world.

Basketball taught me discipline, leadership, and resilience—qualities that have shaped how I approach physics. Just as leading my team required strategy and adaptability, tackling complex equations and scientific principles demands persistence and problem-solving. My goal is to pursue a career in engineering and physics, where I can apply these skills to push the boundaries of what’s possible.

Marian "Nana" Rouche Memorial Scholarship

Erwin Schrödinger was just a name in my physics textbook until the second day of my quantum information program at Stony Brook. That was when I first heard about his famous thought experiment, Schrödinger’s cat. The idea that something could exist in two states at once until observed sounded impossible. I remember thinking there was no way this could be true. But as the week went on, I realized how wrong I was. Superposition wasn’t just sci-fi baloney—it was the foundation for something world-changing. It was the reason I saw a future for myself in the energy field.

Before Stony Brook, I had only read about quantum computers in a few news articles, but I didn’t understand how much they could change energy technology. Traditional computers are reaching their limit—bits can only get so small. We’ve gotten to the point where bits are the size of atoms. Yet, even with all the bits in the world, we are stuck testing one possibility at a time. Quantum computers, however, can process simulations thousands of times faster with a fraction of the hardware. That means years of trial and error will be gone. Whether it’s finding the most efficient solar panel materials or optimizing energy grids, quantum computing could condense that time into days or even hours.

And then there’s space. One of the biggest challenges with quantum computers is that they need freezing temperatures to function. So I thought—what if we sent quantum computers into orbit, using the natural cold of space to keep them stable? From there, they could be integrated into satellites, processing massive amounts of data, improving communications, even helping us develop better energy solutions down on Earth. I don’t know exactly how this would work yet, but that’s the best part. Where’s the fun in knowing how everything will work without trying it out?

I’ve fought for every inch of progress, and I will keep fighting—not just for myself but for those who come after me. I will step into spaces where Hispanics have been underrepresented, not just to take up space but to make room for others. I will push past expectations and prove that our voices, our stories, and our successes matter.

Right now, everything I know is still theoretical. I haven’t had the chance to put these ideas into practice yet, but that’s why I’m here. The financial burden of higher education is something I can’t ignore, and this scholarship would allow me to focus on my studies and research instead of worrying about how to afford it. I want to get my hands dirty in the labs at Cornell. I want to start putting my ideas into practice.

There are energy problems that haven’t been solved yet, solutions that haven’t even been imagined, and I want to be the one to find them. I want to be the one who connects quantum physics, aerospace, and energy. Why? Because I saw a cat in a box once.

Hispanic Achievement Scholarship

Erwin Schrödinger was just a name in my physics textbook until the second day of my quantum information program at Stony Brook. That was when I first heard about his famous thought experiment, Schrödinger’s cat. The idea that something could exist in two states at once until observed sounded impossible. I remember thinking to myself that there was genuinely no way for this to be true. But as the week went on, I started to realize how wrong I was. Superposition wasn’t just some sci-fi baloney, it was the foundation for something world-changing. It was the reason I saw a future for myself in the energy field.

Before Stony Brook, I heard of quantum computers ever so often when reading a few articles, but I didn’t understand just how much they could change the way we approach energy. Traditional computers are reaching their limit in what they can compute as the size of bits can only get so small. We’ve gotten to the point where we have bits the size of atoms. Yet, even with all the bits in the world we are stuck testing one possibility at a time. However, quantum computers can process simulations thousands of times faster with a fraction of the hardware. The years of trial and error will be gone. Whether it’s finding the most efficient solar panel materials or optimizing energy grids, with quantum the time needed could be condensed into days or even hours. The idea that quantum computing could completely reshape the way we develop sustainable energy solutions hooked me.

And then there’s space. One of the biggest challenges with quantum computers is their need freezing temperatures to function. So I immediately thought of space. What if we could send quantum computers into orbit, using the natural cold of space itself to keep them stable enough to operate effectively? I started thinking about how from there we could integrate them into satellites, processing massive amounts of data, improving communications, even helping us develop better energy solutions down on Earth. I have no idea exactly how this would work yet, but that’s the best part. Where’s the fun in knowing how everything will work without trying it out?

I’ve fought for every inch of progress, and I will keep fighting for myself and those who come after me. I will step into spaces where Hispanics have been underrepresented, not just to take up space but to make room for others. I will push past the expectations placed on me and prove that our voices, our stories, and our successes matter.

Moving forward, I refuse to be just another statistic, another story of potential left unrealized. I will continue to break barriers, challenge expectations, and uplift those who come after me. The Hispanic community is not just part of this country’s future—it is central to it. Right now, everything I know is still theoretical. I haven’t had the chance to put these ideas into practice yet, but that’s why I’m here. I want to get my hands dirty in the labs that Cornell offers. I want to start putting my ideas into practice. I want to begin changing the world now, I can no longer wait. There are problems in energy that haven’t been solved yet, solutions that haven’t even been imagined, yet I want to be the one to solve them. It was Schrödinger who opened Pandora's box when I learned of his theory, and now I find myself wanting to be the one who's able to connect quantum physics, aerospace, and energy. Why? Because I saw a cat in a box once.